Previous Posts

Artist Marnie Weber to Premiere New Film

Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions and multidisciplinary artist Marnie Weber will premiere her latest film, "House of the Whispering Rose" (2025), on Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025, at the Philosophical Research Society in Los Feliz. Also featured will be Weber's film "Song of the Sea Witch" (2020).

Following the screening, LACE's Curator and Director of Programs Selene Preciado and Weber will discuss the making of the films and her collaborations.

Weber was a member of the Party Boys, an influential Los Angeles punk band of the 1970s & '80s — the first band to headline at Al's Bar in 1980. She has exhibited her films and artwork all around

the world.

Light refreshments will be provided. The event is FREE, but reservations are required.

Monuments Man

Before the “Young Turks,” before the first punk band played at Al’s Bar, before just about any artists colonized the empty buildings of downtown, Kent Twitchell was creating monumental works on the looming walls of Los Angeles.

"Bride & Groom" on the Victor Clothing Building at 240 S. Broadway. The mural was started in 1972, and Kent Twitchell lived on the top floor of the building until its completion in 1976.

"Bride & Groom" on the Victor Clothing Building at 240 S. Broadway. The mural was started in 1972, and Kent Twitchell lived on the top floor of the building until its completion in 1976.

An iconic part of the downtown landscape, his “Bride & Groom” has adorned the Victor Clothing Building on Broadway for more than four decades. Twitchell lived on the top floor while he was

working on it, paving the way for the historic building’s other creative tenants, such as artists Andy Wilf, Linda Frye Burnham and Richard Newton.

An avid movie buff, Twitchell moved to L.A. from Lansing, Mich., in the mid-1960s, after serving as an illustrator in the Air Force. He studied at Cal State L.A. and Otis Art Institute, all the while

pioneering “street art” with murals featuring frank, bold portraits culled from popular culture.

His earliest efforts include stunning depictions of his movie heroes, Steve McQueen and Strother Martin. Both murals were completed in 1971 and still exist in their original locations.

"Steve McQueen" (left) is at 12th & Union streets, near downtown L.A.; "Strother Martin" can be seen at 5200 Fountain Ave. in Hollywood.

"Steve McQueen" (left) is at 12th & Union streets, near downtown L.A.; "Strother Martin" can be seen at 5200 Fountain Ave. in Hollywood.

A few of his greatest and most memorable murals, however, were lost to ignorant or unappreciative building owners, although these losses spawned landmark lawsuits that bolstered rights for creators of public art.

Twitchell’s “Freeway Lady” graced the Hollywood Freeway in Echo Park for 12 years after its debut in 1974, before being illegally painted out in 1986. The

Afghan-draped woman was recently re-created at L.A. Valley College on Fulton Street in Valley Village.

From 1978 to 1987, Twitchell toiled on a labor of love, an imposing and impressive monument to one of the greats of Los Angeles art, painter Ed Ruscha. For

nearly two decades, the portrait of a civic and national treasure confronted passersby from the building near 11th and Hill, only to be mistakenly painted out without warning in 2006.

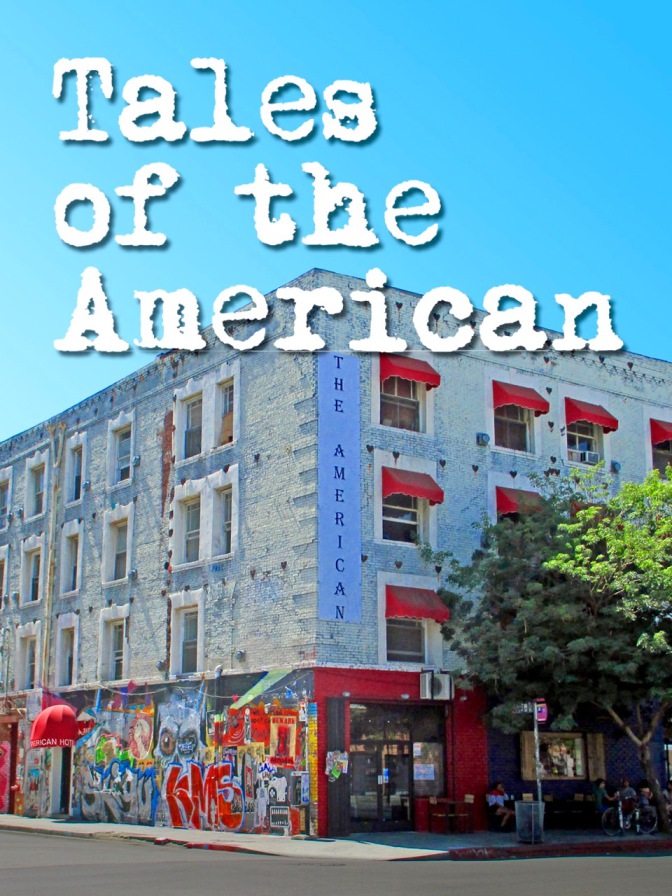

Earlier this month, Kent Twitchell began installing his new “Ed Ruscha Monument” on the western wall of the American Hotel in the Arts District. His subject is depicted as older and perhaps wiser, peering over adjacent rooftops with laced fingers and an even, reassuring gaze.

Harry Bosch in the Arts District

In Michael Connelly’s new novel, “The Wrong Side of Goodbye,” iconic detective Harry Bosch follows the trail of his case into L.A.’s Arts District. He’s a private eye now, after being forced out of the LAPD, and his investigation draws him to Traction Avenue and landmarks such as the American Hotel and the triangle lot between 3rd & Rose.

Bosch is one of the great characters of mystery fiction, right up there with Philip Marlowe, and like Marlowe’s creator, Raymond Chandler, Connelly paints a haunting and vivid picture of Los Angeles and the Southland in all his Bosch books, including “The Wrong Side of Goodbye.” As the New York Times writes, “the settings will be etched into the Bosch road map of California life.”

Pamela Wilson and Stephen Seemayer, filmmakers of “Young Turks” and “Tales of the American,” are very proud and honored to have shared some insights with Michael Connelly in the preparation of this book.

“Tales of the American” is in post-production, but “Young Turks” can be viewed on all digital platforms, including Amazon Prime, which also is producing the TV series, “Bosch,” now filming its third season.

The Low Down on High Art

Coagula Art Journal was produced for many years in a small room at the American Hotel. Starting in 1992, Editor and Publisher Mat Gleason singlehandedly produced the rebellious, often controversial, underground take on the art world, distributing it free in galleries and museums throughout the Southland.

As a tenant of the hotel, Gleason says, “If someone wanted to put an ad in Coagula, they had to stand out in the street and yell up, ‘Mat! Mat!’ There was no email, there were no cellphones. It was like the 19th century.”

A few years ago, Gleason began publishing Coagula as a digital-only journal. Now it is now in print once again, and available all over the country.

Gleason also runs a Chinatown gallery, Coagula Guratorial, on Chung King Road.

Downtown Pioneers

In two recent articles, Los Angeles Times writer Carolina A. Miranda reminds Angelenos that there were artists, galleries and others in the Arts District before it was called the Arts District.

Stephen Seemayer walks from Downtown Los Angeles to San Diego with a cross on his back, as documented in "Young Turks."

Stephen Seemayer walks from Downtown Los Angeles to San Diego with a cross on his back, as documented in "Young Turks."

Stephen Seemayer, artist, filmmaker: "It was very bleak. There wasn’t crack yet. There wasn’t AIDS. But there was a sense of desolation. It was so desolate that even the cops didn’t really want to deal with you. I was 3 to 4 blocks away from the Newton Division and it’s famous in the LAPD. They were called the 'Shootin’ Newton.' I was like 22 at the time. I would be there at my studio and they’d see me out of my car and they’d roust me and said, 'What are you doing in this neighborhood?' And I’d say, 'I live here.' And they’d say, 'Get out!'"