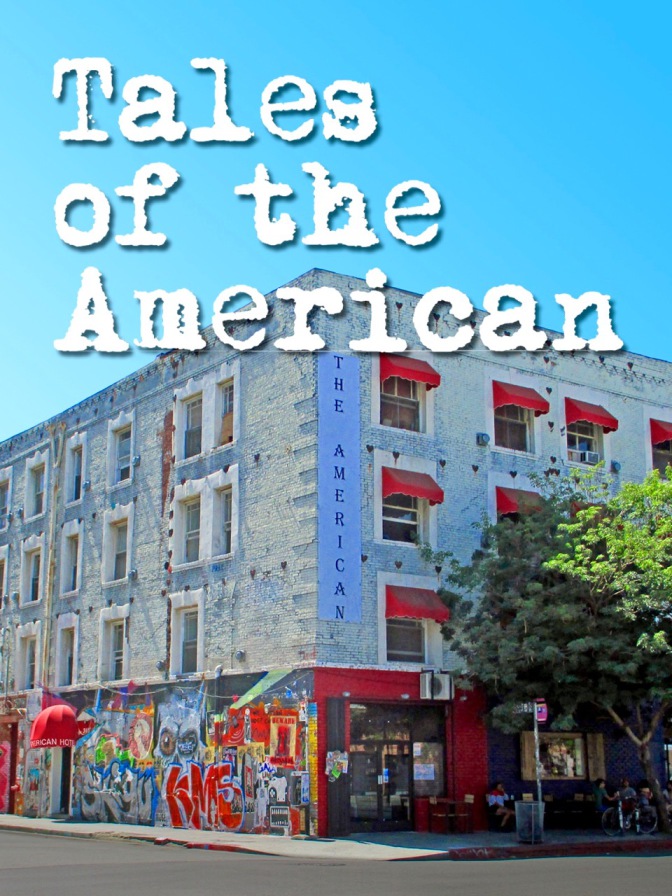

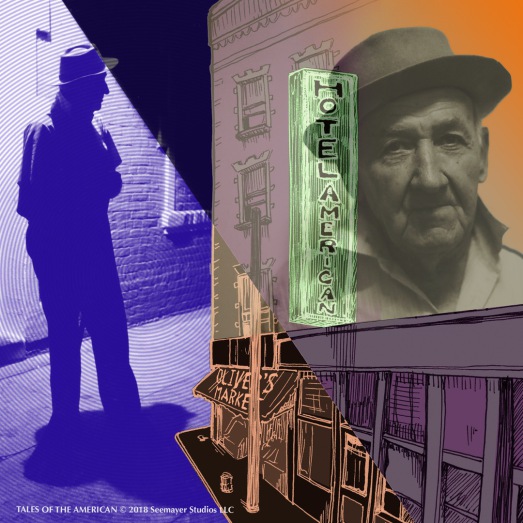

POSTcards From the Past

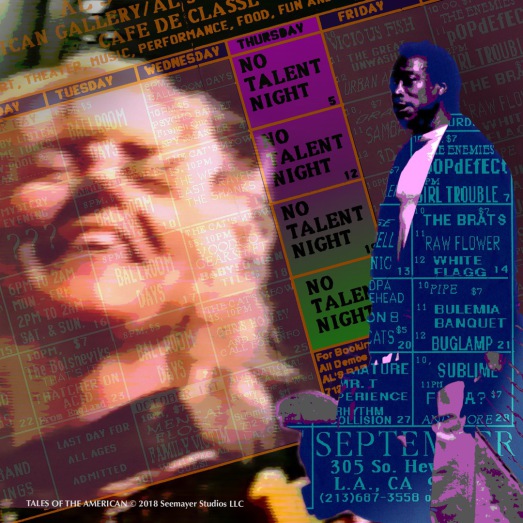

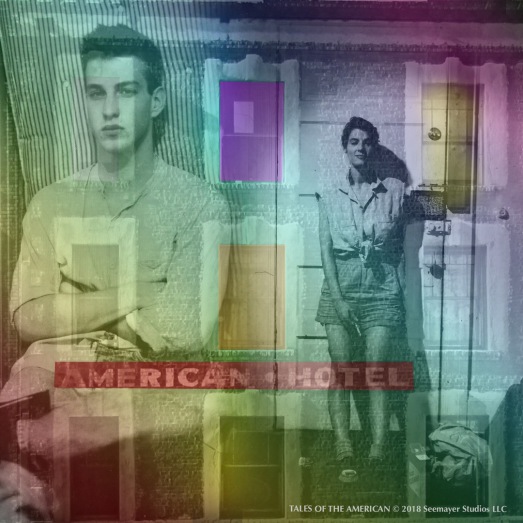

From its earliest days as L.A.'s first black hotel, the four-story building on the corner of Hewitt Street and Traction Avenue has been a witness to the city's evolution throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. "Tales of the American" dives right back to the start, in 1905. Through interviews, photos and archival footage, the documentary weaves a colorful tapestry of events, memories and characters that have played central roles in the life of the American Hotel.

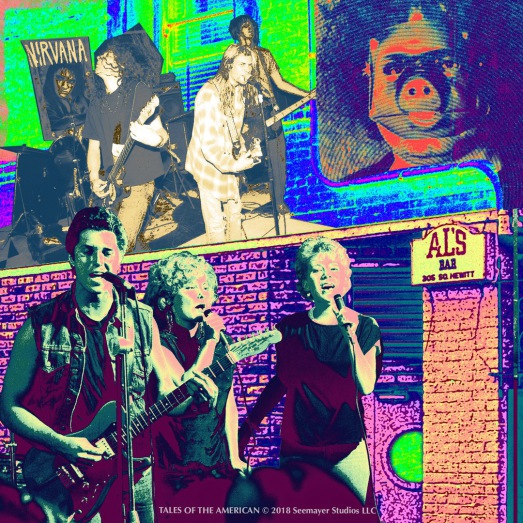

---- 2018 ----

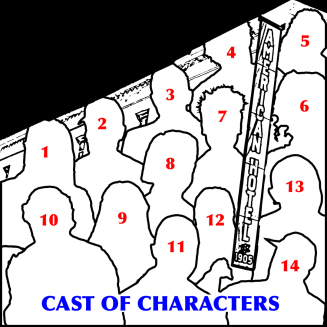

"The American Hotel was a stew of dreamers, malcontents, psychopaths, outlaws, artists, musicians and writers who gathered together to form a community that stamped an indelible mark on the buildings and streets of the Arts District and beyond," writes Los Angeles author Rick Leddy. The filmmakers of "Tales of the American" interviewed more than 140 of these colorful characters.

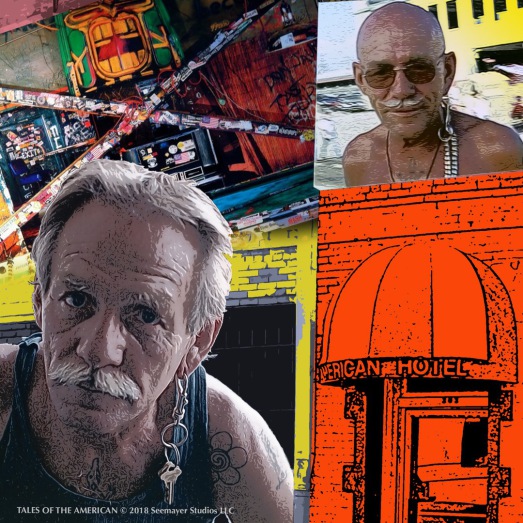

1) TOAST BOYD, musician & manager of Al's Bar & the American Hotel, now builds & repairs

2) ROCCO ROSSI, longtime tenant of the American who died in 2017

3) LLOYD KIBBEE, homeless man who befriended hotel tenants

4) STEVIE CASUAL, guitarist & tenant of the American Hotel who passed away in the fall of 2017

5) ALBERTO MIYARES, multimedia artist with studios in L.A. & Landers

6) STAY-C (Little Cannizzaro), rapper & longtime bartender at Al's, now a mother of two in Vermont

7) 'BIG AL' WATT, collector & raconteur who lived in the hotel until his death in February 2015

8) TERRY ELLSWORTH, curator, arts coordinator with Artshare L.A. & American Hotel resident

9) JETT JACKSON, painter & former hotel tenant now living in Buffalo

10) RICHARD DUARDO, late founder of Modern Multiples printmakers

11) WILLIAM MITCHELL, dancer & artist who died in February 2013

12) KIMBA ROGERS, former Al's bartender now designing T-shirts

13) JIM FITTIPALDI, creator of Bedlam Art Salon who died in Florida in 2016

14) FRANK PARKER, homeless artist made & sold 'frangs' (bracelets made from scrap wire), died in 2001

---- 2007 ----

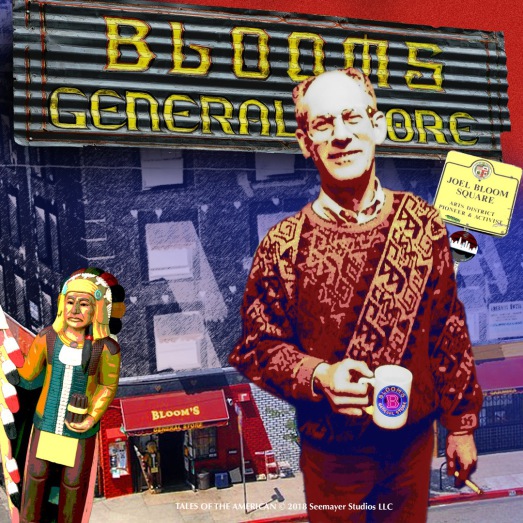

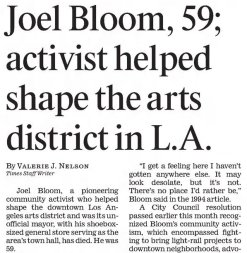

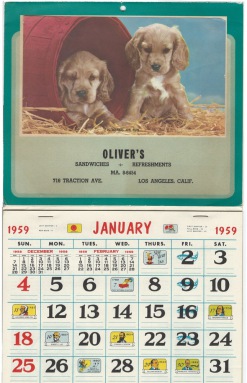

In 1995, Joel Bloom opened Bloom's General Store on the ground floor of the American Hotel. The corner market quickly became the hub of the growing artist community. As an advocate for the gentrifying area remaining a haven for artists, Bloom's impact on the neighborhood was immeasurable, and before he died in 2007, the city named part of Traction Avenue after him.

---- 1991 ----

Since the 1980s, the American Hotel has been an ever-changing canvas for street artists and muralists, including SK-8, Kent Twitchell, Nuke One of the UTI crew,

calligraffitist Peter Greco and "Angel Wings" artist Colette Miller. The Hewitt Street wall in particular — starting in 1991 with Aaron "SK-8" Anderson's iconic

"LA" mural — has been "like a living organism, alive with beauty," says graffiti photographer Irving Greines.

---- 1989 ----

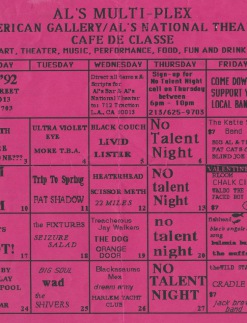

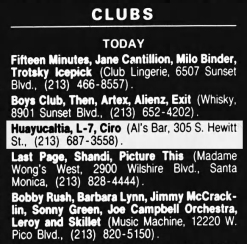

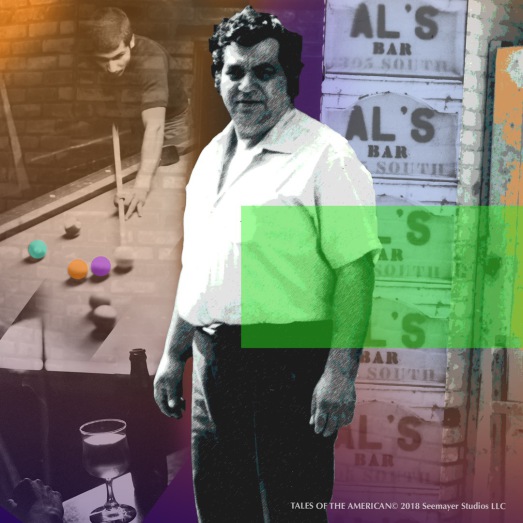

From the reggae vibes of Jesse Easter's Barbed Wire to the grunge rock of Nirvana, the variety of bands that played Al's Bar in the 1980s was remarkable. Top Jimmy & the Rhythm Pigs — featuring Carlos Guitarlos — was one of the earliest groups to play on the Al's Bar stage. "Al's Bar was really Ground Zero for interesting, creative music," says John Collinson, drummer for Leather Hyman.

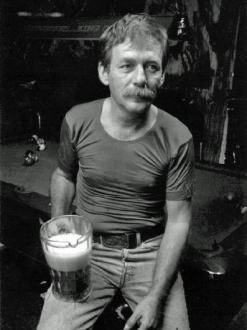

Don Jones — or Dr. Jones as many called him — was a vagabond, a raconteur and the "King of Downtown." Jones bought knickknacks at thrift stores and then resold them, spinning fabulous tales of their origins for prospective buyers. He moved into the American in 1984 and lived on the third floor for the better part of a decade.

---- 1982 ----

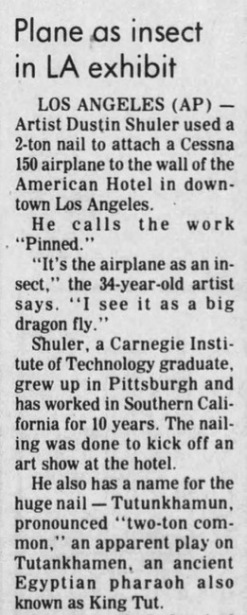

In September 1982, artist Dustin Shuler made national headlines when he nailed a full-size Cessna to the side of the American Hotel. The installation was meant to be temporary, but for a variety of reasons — including a lawsuit — the artwork remained attached to the hotel for four years.

---- 1980 ----

In 1980, the American Hotel became a haven for artists in need of affordable living space, one of the first such buildings in the area now recognized as the Arts District in downtown Los Angeles. The hotel also was one of the venues for "Public Spirit," a groundbreaking festival which drew performance artists from around the world.

---- 1973 ----

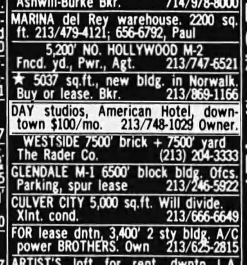

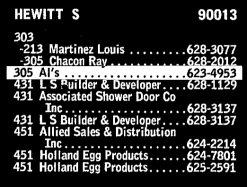

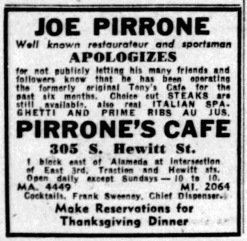

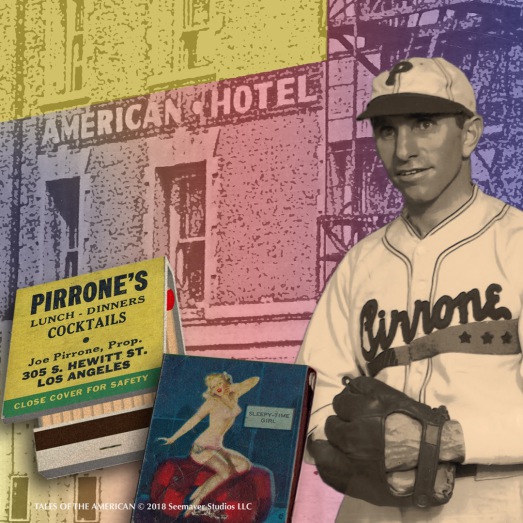

The Hewitt Street storefronts at the American Hotel housed many businesses over the years — the Golden West, Tony's Café and Joe Pirrone's to name a few. But in 1973, Alfonso Vasquez opened a bar there and named it after himself. Al's Bar began as a hangout for local truck drivers and factory workers. They could stop by after a long day for a cold beer and a friendly game of pool. Then a shift in the neighborhood's demographics led to a change in the bar's clientele.

---- 1961 ----

"Old George" was what tenants called George Zarvis, the resident handyman of the American Hotel. Once a wheelman for a stick-up gang, George moved into the hotel in 1961 and never left. "George was just part of the scenery," says former Al's bartender Sandi Cruze. Old George died in his room at the hotel in 1997. He was 86.

---- 1946 ----

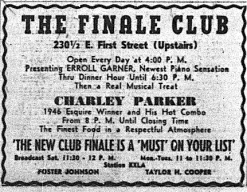

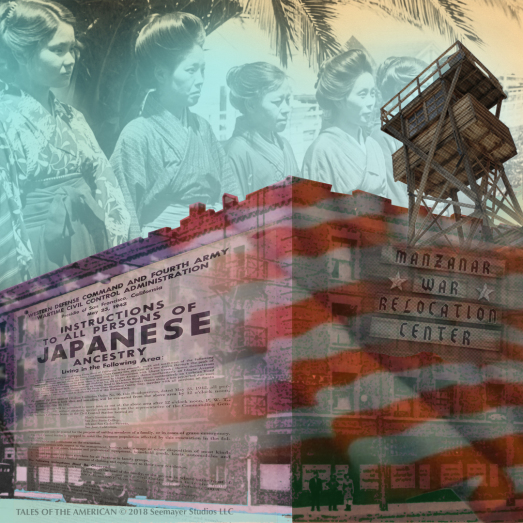

The internment of its 30,000 residents left Little Tokyo a ghost town, but an influx of 80,000 mostly black workers and their families, drawn by wartime defense jobs, quickly repopulated the area, including the American Hotel. It led to overcrowding and so-called "slum conditions," but it also reinvigorated nightlife as jazz venues, featuring greats like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis, opened around what had been Little Tokyo's core.

---- 1944 ----

Native Angelino Joe Pirrone was the driving force behind the California Winter League, which — decades before Jackie Robinson — featured black and white pros playing baseball together on diamonds around Los Angeles. In 1944, Pirrone opened a restaurant on the ground floor of the American Hotel. Pirrone's Café operated there for more than a decade.

---- 1942 ----

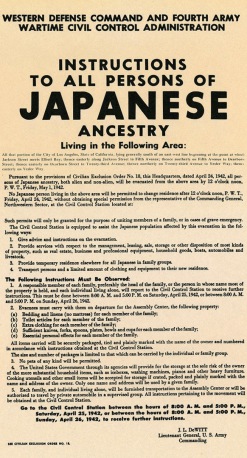

By World War II, the population of the American Hotel was mostly Japanese. Pearl Harbor changed all that. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, ordering the "evacuation" of all Japanese on the West Coast. Within three months, virtually all residents of the hotel and surrounding Little Tokyo were shipped off to internment camps.

---- 1935 ----

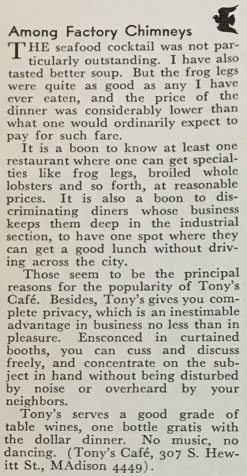

Long before Al's Bar occupied the space, Tony's Café — a popular neighborhood restaurant — opened on the ground floor of the American Hotel. A 1935 Westways article called its frog legs "quite as good as any I've ever eaten," and a bottle of wine came with the $1 dinner. Owner Tony Panzich, a notorious local bootlegger, was sent to prison just as the restaurant was opening on Hewitt Street in 1933. In his absence, Panzich's wife, Mary, managed the café, which operated until 1943.

In the early 20th century, anti-Asian sentiment — culminating in the "Exclusion Act" of 1924 — kept L.A.'s Japanese popuation localized in the Little Tokyo area. When Kintaro Asano took over managing the American, he saw opportunity in providing lodgings for his fellow immigrants. He even renamed it the Hotel Bitchu, after a province in his homeland. Asano turned the corner storefront into a market and leased it to a fellow immigrant named Genjiro Nakamura, who sold groceries out front while he and his family lived in the back.

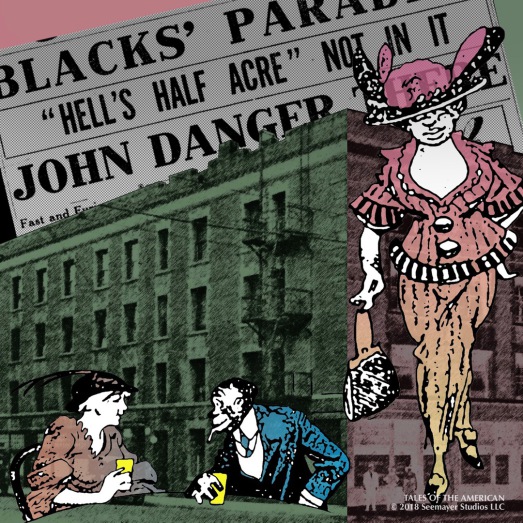

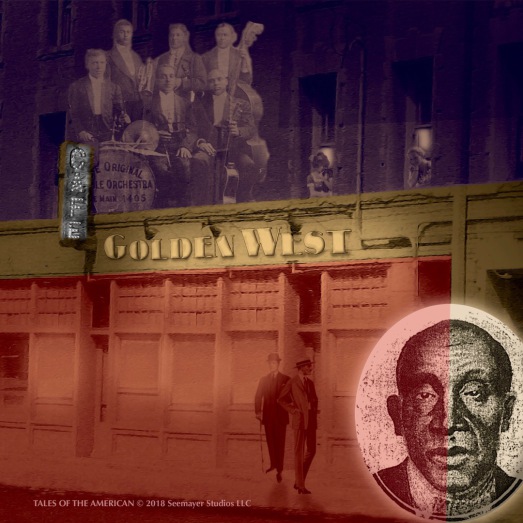

In 1914, a muckraking L.A. Record reporter calling himself John Danger published a series of scandalous exposés of city nightlife. One target was the Golden West Café on the ground floor of what would later be called the American Hotel. Danger described the café as a raucous place, and one of the few bars in L.A. where black and white patrons could drink and party together. Danger's "gutter journalism," as The Times called it, caught the eye of city officials, who soon shut down the Golden West.

When George Brown, known as “king of the underworld,” hired the Original Creole Orchestra — with Freddie Keppard and Bill Johnson —to play in his Golden West Café, he helped introduce jazz to the City of the Angels. Brown also ran the hotel above, later renamed the American. Brown's Golden West Café would eventually be shut down by the city, but he would go on to help establish Central Avenue as the cultural hub of L.A.'s black population.

---- 1906 ----

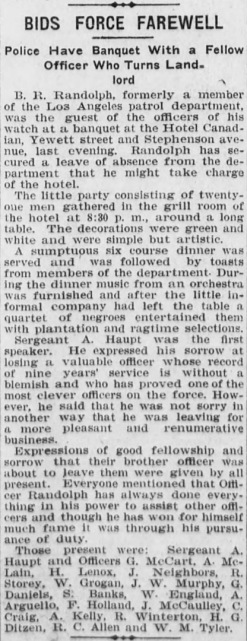

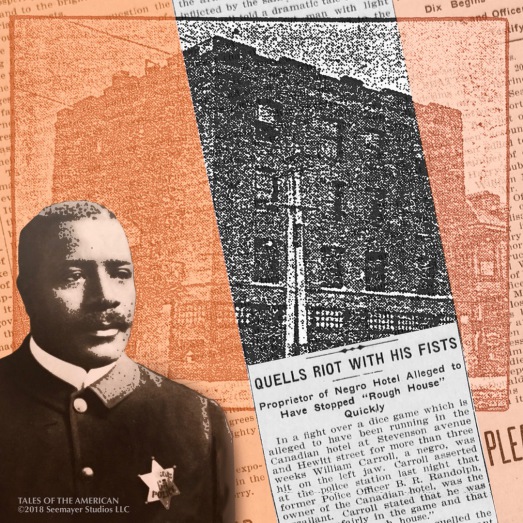

Berry R. Randolph was the LAPD’s only black police officer in 1906 — and just the second in the department's history — when he turned in his badge to become the manager of the American Hotel, at the time the city’s only hotel for African Americans. Then known as the Canadian, it earned a reputation as a "rough house" after numerous reports of gambling, vice and violence.

---- 1905 ----

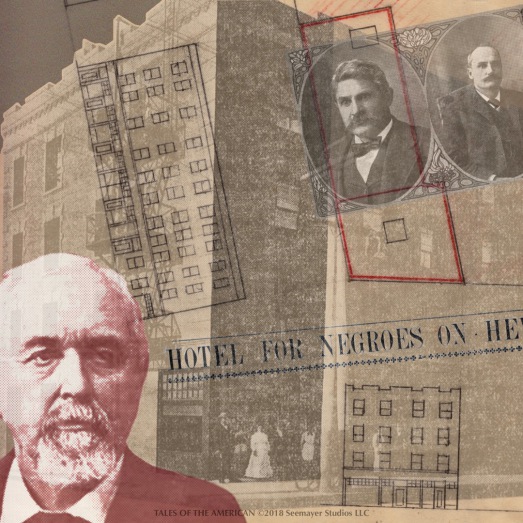

Spurred by a P.R. disaster for the City of Los Angeles, businessman William H. Avery hired architects Octavius Morgan and John Walls to build the first hotel in L.A. — then called the Canadian — specifically meant to provide lodgings for African Americans.